Valence bond structures and Catalan numbers

The Valence Bond theory (VB) describes chemical bonds in molecules. It is an alternative description to the familiar Molecular orbital (MO) theory. The main difference between the two being that in VB theory the valence electrons participating in a covalent bond are thought to be localized on their atoms and the bonding is described as the overlapping of the electrons on different atoms. In MO theory on the other hand the electrons are described as delocalized over the molecule. In MO theory new orbitals are formed as linear combinations of the atomic orbitals leading to bonding and anti-bonding orbitals. In VB theory one looks at all possible structures a molecule can have which include covalent, ionic and possibly other structures. All of these structures described by appropriate Slater determinants are superposed with some coefficients. By optimizing the coefficients of the different structures to minimize the energy one gets the full wave function of the electrons in the molecule which describes the electron probability density in the molecule.

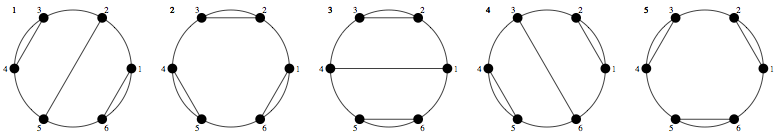

A famous example of this is the Benzene molecule \({\rm C_6H_6}\) consisting of 6 carbon atoms in a ring and 6 Hydrogen atoms bonded to them. In the Benzene case since carbon has 4 valence electrons one is used in the Hydrogen bond and two are used to bond with the neighboring C atoms. The remaining electron can bond with either one of the neighboring C atoms (2 Kekule structures) or with an opposite C atom (3 Dewar structures). Thus in total there are 5 possible covalent structures for the Benzene molecule which should be taken into account when calculating the total wave function of the molecule. As stated, there are also ionic structures which should be taken into account in which two electrons are localized on on atom. I will return to these structures later.

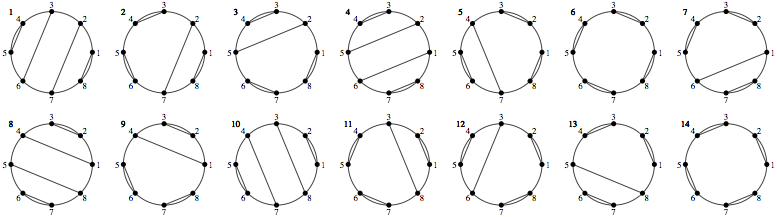

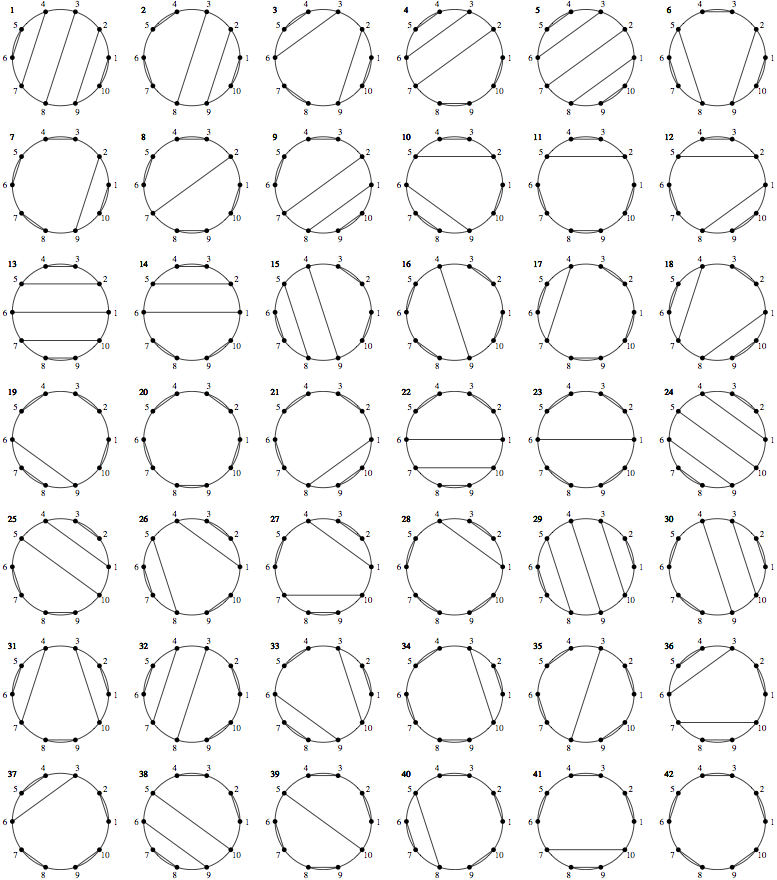

The structures are shown with the carbon atoms on a circle with the circle and lines representing bonds between them and the H atoms are omitted.

For 6 atoms it is an easy task to find all the covalent structures by hand. However already for 8 atoms this becomes a rather daunting task. Here I will present first how to calculate the total number of these structures for a given number of atoms and how to draw them automatically.

This is now a problem in the field of discrete mathematics or combinatorics, motivated by the background given above. This counting problem can actually be casted to the party hand-shaking problem, where an even number of people are shaking hands on a circular table without crossing. Or more abstractly just connecting points on a circle without crossing, and with one line going from each point. In order to calculate the number of such hand shakes for a given number of points n (\(a_n\)), we number the points from 1 to n and pick a random point \(i\) other than 1 and connect that point with the first point. This divides the problem into two similar problems with less points. The first half has \(i-2\) points which will be connected to each other following the same rules, and the second half has \(n-i\) points. For this choice of point \(i\) there are \(a_{i-2}a_{n-i}\) “structures”. Summing over the possible choices of \(i\) We therefore get the following recurrence relation: \(a_n=\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n/2} a_{2i-2}a_{n-2i}\), where the use of $2i$ causes the i to jump in increments of 2, from \(2\) to \(n\). The jumps by 2 is necessary in order to prevent isolated points.

This recurrence relation gives the Catalan series with \(a_n=C_{n/2}\). The first Catalan numbers for \(n=0,1,2,3,4,5,6,....\) are \(1, 1, 2, 5, 14, 42, 132,...\) These can be calculated using the explicit formula: \(C(n)=\frac{1}{n+1}\binom{2n}{n}\). The Catalan numbers appear again and again in various counting problems. One such problem which turns out to be relevant to the second part of our problem, namely drawing the structures. This problem is that of arranging \(2n\) parentheses consisting of \(n\) parentheses of each type in legal ways. The number of such arrangements turns out to be equal to \(C(n)\). For example for n=6, the possible legal “words” are ((())), (()()), (()(), ()(()), ()()(). This one-to-one correspondence between the two problems suggests a way to find and draw all the possible structures, since there is a standard way of obtaining all the legal words of the kind shown (also called Dyke words). The first \(n/2\) points, numbered from \(1\) to \(n/2\) on the circles correspond to an opening bracket and the remaining \(n/2\) numbers to a closing bracket. Then each pairing of points corresponds to an opening and closing bracket, and the no crossing condition guarantees only legal words. The code for generating all the Dyke words of length \(2n\) is given below with the modification of calling “(“ “1” and “)” “0”. The code uses a clever recursion:

structs=[]

def words(l,r,ss):

if (l==0 and r==0):

structs.append(ss)

if (l>0):

words(l-1,r+1,ss+"1")

if (r>0):

words(l, r-1, ss+"0")

Then we call this function using:

words(num/2,0,"")

This will put all the legal words as strings in the structs array.

The next step is to convert these words consisting of 0’s and 1’s to the indexes of the points on the circle so that it can later be used to know which points are connected by a line. For example the word “110010” corresponding to the bracket word “(())()” and to the sequence of numbers on the circle 142356 which is to be interpreted as 1 is connected to 4, 2 to 3 and 5 to 6.

The function which does the conversion is given below.

pairs=[]

def convert():

for s in structs:

news=[]

for i,l in enumerate(s):

if l=="0":

continue

count=1

news.append(i+1)

for j in range(i+1,len(s)):

if s[j]=="0":

count=count-1

if count==0:

news.append(j+1)

break

else:

count=count+1

pairs.append(news)

The function goes over the word. When it sees a “1” it sets a counter on 1 and adds the place of this 1 as an entry in the numbers sequence. Then it goes over the rest of the word beyond that place. Each time it encounters another 1 the counter is incremented by 1, if it encounters a 0 it reduces the counter by 1. If the counter is 0, it means that we’ve reached the closing bracket “0” of the initial opening bracket “1” and we save the place of that closing bracket as the number which is to be connected with the previous number entered.

The full program creates a .csv file which lists all this sequences of possible structures. This file is then used in Mathematica to draw the structures.

The full python code is here, and the Mathematica notebook here.

Bellow I show the results of the program for $n=8$ and $n=10$ giving 14 and 42 structures respectively as expected.