Fractals

Fractals are unique mathematical objects with interesting properties and surprising manifestations in nature. They are obtained by usually a simple rule that is repeated recursively, leading to intricate self-similar structures repeating on all scales, making them scale free. This intricate pattern might suggest an infinite amount of information is required to describe such an object, however the power of their complexity is in the simplicity of the generating rule together with the feedback or recursive application of this rule.

Fractals were found to be tightly related to chaos theory, and they naturally appear in systems on the edge of chaos, such as in turbulent flow, and population growth described by the logistic equation.

Fractals (or near fractals) having self-similar features are also pervasive in living systems, examples of which are the surface of the brain, the lungs surface, arteries and veins, in which the fractal nature is crucial for their functionality. Fractals are found in plants and trees, as well as non-biological systems, such as in mountain ranges, rivers, clouds and coastlines.

The infinitely intricate structure of fractals leads to a curious geometrical property related to their dimension which can be non integer or fractional, i.e. somewhere between a point and a line, or between a line and a square or between a square and a cube.

Below I show a few of the common toy fractals all having a simple rule which was recursively applied.

Cantor set

The Cantor set, named after the mathematician Georg Cantor is obtained by recursively removing the central third of a line. This then leads in the limit of infinite recursions to a set of infinitely many points with measure zero.

Koch fractal

The Koch fractal is obtained by replacing the central third of a line by an equilateral triangle without the bottom part. When starting with a triangle we get the Koch flake.

Sierpsinski triangle

The Sierpinski triangle is obtained by repeating drawing a triangle between the central points of the sides of each formed triangle.

Tree fractal

The tree fractal is obtained by drawing two branches from each line at a fixed angle to the line and reducing the size of consecutive branches by a constant factor.

Fractal dimension

The fractal dimension can in some cases be obtained be a generalization of the more familiar notion of a dimension for objects such as lines, squares and cubes. We have that an n-dimensional object can be constructed by $N=m^n$ copies of itself each scaled by $1/m$. The dimension is then given by $n=\log_m N$. For example, a line divided by half (m=2), has two copies of itself, giving $2^n=$ and $n=1$, similarly for a square with sides halved we have $2^n=4$ giving $n=2$, and similarly for a cube we have $2^n=8$.

Applying this to the Koch fractal for example, in the second generation of the generating rule, we have 4 copies of the original object all scaled by a factor $1/3$ giving $3^n=4$ giving for the fractal dimension $n= \log_3 4\approx 1.26$. Great Britain’s coast line was measured to be a fractal with dimension 1.25, similar to the Koch fractal.

Similarly for the Cantor set we have in the second generation, 2 copies of the original scaled by a factor of $1/3$ giving $3^n=2$ and a fractal dimension of $n=\log_3 2 \approx 0.63$.

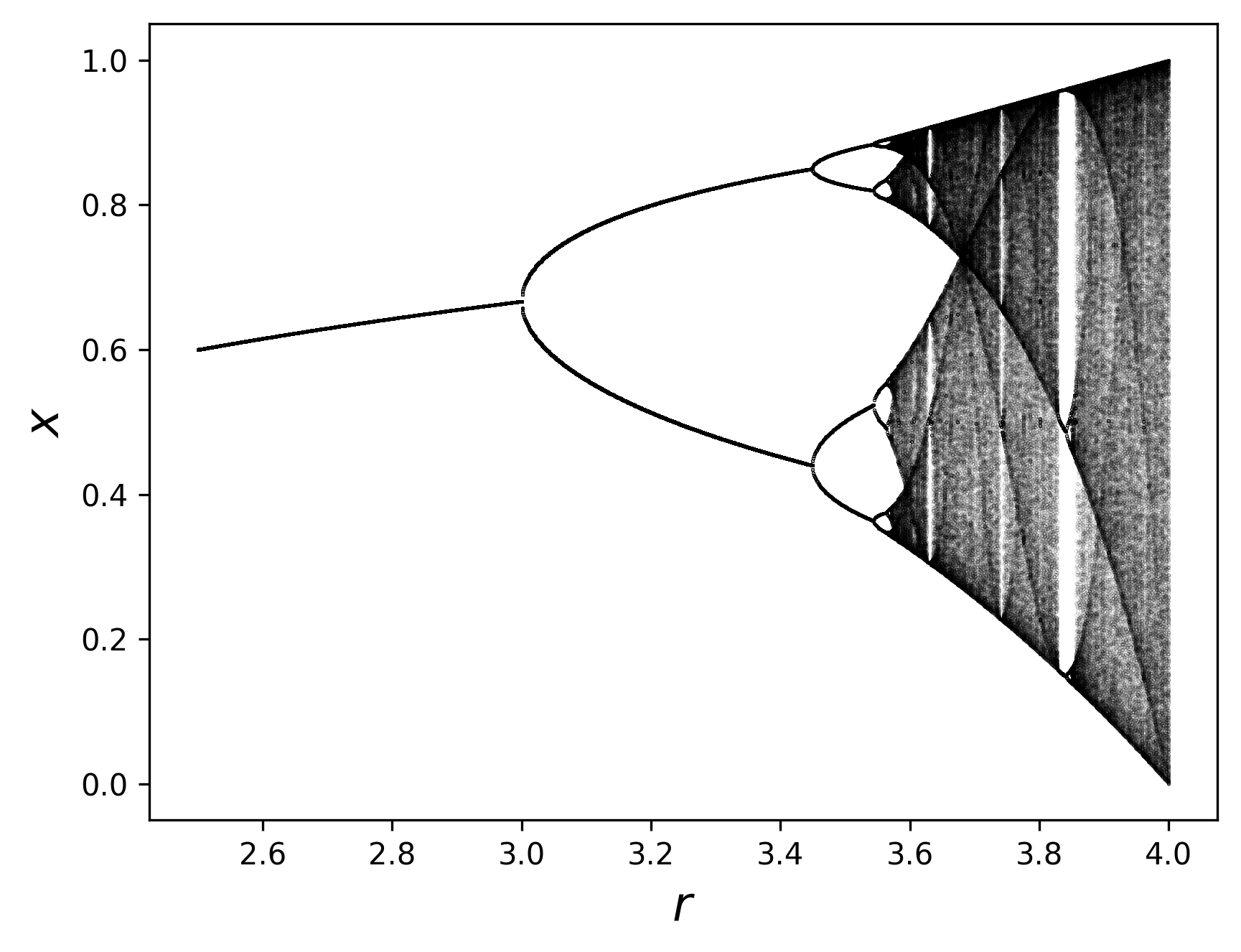

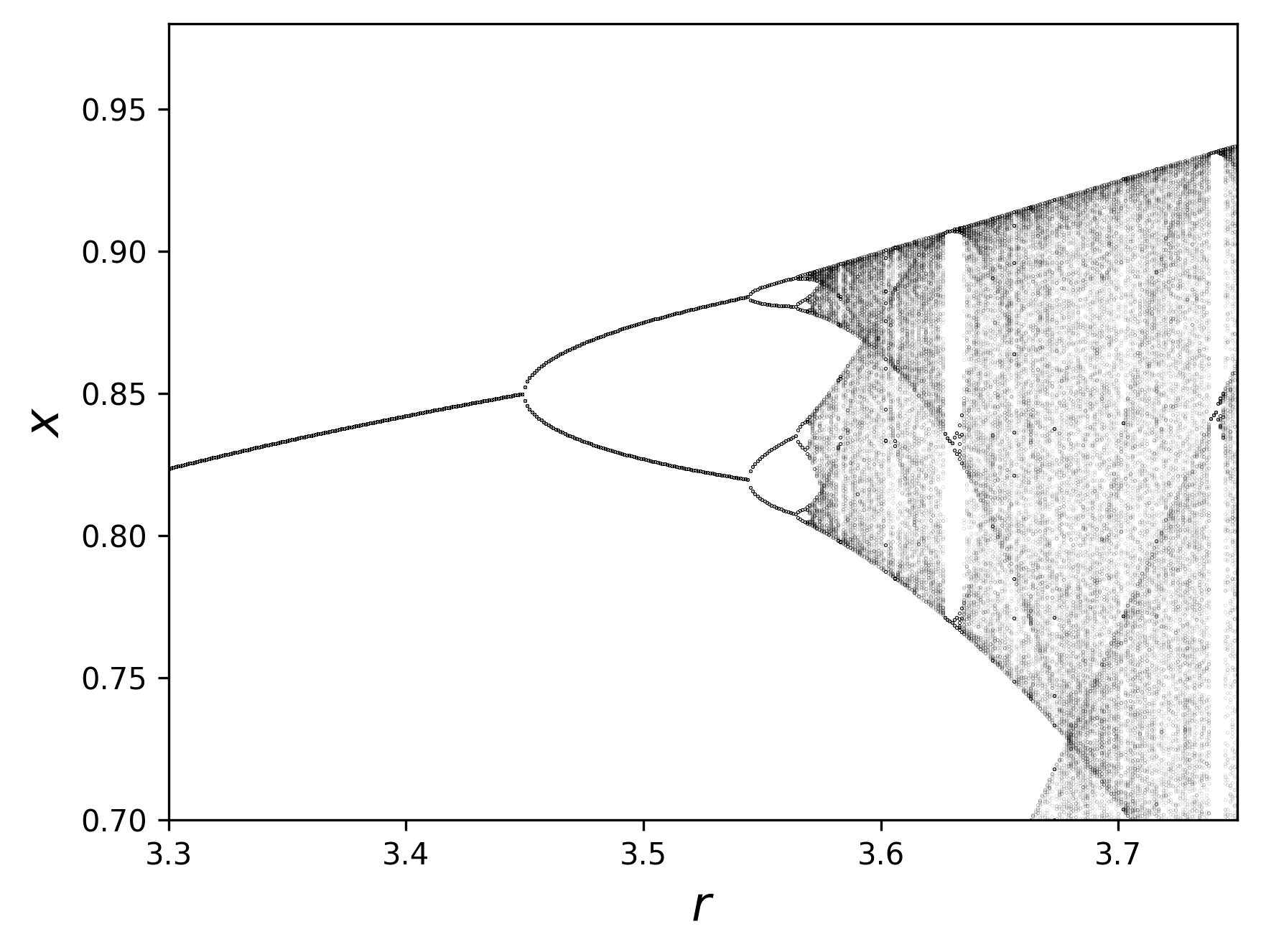

As mentioned in the beginning, fractals commonly appear in dynamical system involving feedback. This is best demonstrated with the seemingly simple rule,

\[x_{i+1}=r x_i(1-x_i)\]known as the logistic model, which describes a population with a growth rate $r$, and $x\in [0,1]$ is the fraction of the population relative to the maximum.

A system described by the logistic model reaches steady state when $x_{i+1}=x_i$ for $i>M$ for some $M$. By plotting the steady state value for different value of $r$ we obtained the famous bifurcation plot below, which has a fractal structure.